JOE |

Dublin is one of the riskiest cities for cybercrime

JOE However, the good news is that researchers said the cities with the greatest cybercrime risk factors did not necessarily correlate with the highest computer virus infection rate. Researchers said that this reflected “the fact that many consumers are ... Dublin sixth riskiest online city, survey says |

Friday, November 16, 2012

Dublin is one of the riskiest cities for cybercrime - JOE

Monday, November 12, 2012

What You Should Expect From Windows 8

What you should expect from Windows 8? Get My Early insights and opinions into Microsoft's upcoming Windows 8 Consumer Preview should give IT departments and consumsures a lot to chew on and contemplate when the Windows 8 Arrives.

With the Windows 8 Consumer Preview beta edition just around the corner, now is a good time to examine what we know and don't know about Microsoft's forthcoming OS, and what IT should look for when the Consumer Preview hits as expected on Feb. 29.

Windows 8 rates as Microsoft's latest bet-your-company move, with the computer industry rapidly adopting mobile platforms. For Windows 8 to thrive in the corporate environment, however, it has to not only add important new capabilities to today's Windows 7 desktop but also morph into a touch-enabled, highly portable, secure OS that IT can tolerate and users will love.

Putting Windows 8 Consumer Preview into perspective No doubt you've already banged around the Windows 8 Developer Preview, and your clicking finger is poised to get the Consumer Preview bits as soon as they appear. But it's worthwhile to step back and take a look at what will, and won't, be happening at the end of the month.

Microsoft isn't trying to convince you to upgrade all of your Windows PCs to Windows 8. Quite the contrary -- last week, Microsoft's general manager of investor relations, Bill Koefoed, gave a short talk at the Stifel Nicolaus Technology & Telecom Conference (video and transcript), where he said, "One-third of businesses have upgraded to Windows 7. ...

For the enterprise, the path to Windows 8 is through Windows 7." Microsoft is far more interested in getting all of your PCs on Windows 7 than they are on pushing your PC users to Windows 8. I have a feeling that's going to come through loud and clear in the Windows 8 Consumer Preview.

For the enterprise, the path to Windows 8 is through Windows 7." Microsoft is far more interested in getting all of your PCs on Windows 7 than they are on pushing your PC users to Windows 8. I have a feeling that's going to come through loud and clear in the Windows 8 Consumer Preview.

"Consumer preview" is a bit of a misnomer anyway. This is a reasonably stable, mostly feature-complete build of Windows x86/x64, where the user interface isn't locked in concrete, and that's it. Microsoft is way beyond the point where substantive changes can be made. Online comments and extensive eavesdropping -- "telemetry" in Microsoft parlance -- may lead to some interface changes. But the plumbing is already in and won't be altered.

The version of Windows 8 that has gotten the most recent buzz, Windows on ARM (WOA) will go out to a very select few; there isn't even a hint of when we unwashed masses will get to see them. We do know that Qualcomm, Nvidia, and Texas Instruments are working on WOA devices -- likely tablets but perhaps touchscreen netbooks as well.

WOA won't have the Windows 7 "desktop" part of Windows 8, so it won't run the familiar Windows Explorer or existing (Win32s) Windows apps. It just runs the Metro UI, a touch-oriented operating environment for lightweight applications, and apps designed specifically for Metro -- sort of like how Apple's iOS is the separate-but-related, light counterpart its Mac OS X. Of course, x86-based PCs get both the Windows 7-derived "desktop" and Metro, whereas Macs can run Mac OS X but not iOS.

What to expect from the Windows 8 user interfaceIf you've been looking at the Developer Preview, you know all about Windows 8's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde interface(s).

You've seen the touch-oriented Metro interface with tiles in reorganizable groups, where the faces of the tiles change programmatically and you can pinch to zoom out to view all of the tiles at once ("semantic zoom"). In the Consumer Preview, Microsoft promises we'll be able to create and name new groups, drag groups, change the background color and style, turn big tiles into little tiles, and use the mouse (not just our fingers) for all sorts of navigational actions, including semantic zoom.

There are several minor changes in the way you swipe and click, particularly with the charms bar (Search, Share, Start, Devices, Settings) on the right. These changes are largely cosmetic, but if you're thinking about deploying a Metro app -- especially a Metro app that has to live in a mouse-friendly world -- they could be crucial.

There are several minor changes in the way you swipe and click, particularly with the charms bar (Search, Share, Start, Devices, Settings) on the right. These changes are largely cosmetic, but if you're thinking about deploying a Metro app -- especially a Metro app that has to live in a mouse-friendly world -- they could be crucial.

Also on the Metro side of the fence, the current, reprehensible App Search behavior changes: Instead of Search splatting an alphabetized list of all your applications on the screen, as the Developer Preview does now, the Consumer Preview arranges them by groups. You'll probably want to work with it a bit, try rearranging and renaming groups, and see if your users can live with the new tools at hand.

On a "legacy" Windows 7-based PC (a loathsome term), more changes are in store. It still appears as if all Windows 7 apps and drivers will just work on Windows 8 PCs -- that is, desktops and laptops using Intel or AMD x86 CPUs.

That's certainly the goal, anyway. In the Consumer Preview, we'll see a few changes: an improved Task Manager with more details and app startup tweaking; the new Windows Explorer ribbon won't appear by default as it does in the Developer Preview (yes, Explorer will still have the "up one level" button, as well as the Open Command Prompt menu item); a few long-overdue tweaks to the copy and move dialogs. They're all worth a look, though nothing's really compelling.

That's certainly the goal, anyway. In the Consumer Preview, we'll see a few changes: an improved Task Manager with more details and app startup tweaking; the new Windows Explorer ribbon won't appear by default as it does in the Developer Preview (yes, Explorer will still have the "up one level" button, as well as the Open Command Prompt menu item); a few long-overdue tweaks to the copy and move dialogs. They're all worth a look, though nothing's really compelling.

The big change in the "legacy" PC version is the Start button. In the Developer Preview, clicking on the Start flag (it wasn't really a button) switched you to the Metro interface. Apparently the Consumer Preview does away with the button, but not the behavior.

As I explained recently, the overriding problem is that the "legacy" Windows desktop doesn't have a "legacy" Start menu. A small cottage industry has grown up with registry hacks and lightweight programs to bring back the Start menu in the Developer Preview. Will Microsoft make it easy for admins and users to unlock the menu in the Consumer Preview?

As I explained recently, the overriding problem is that the "legacy" Windows desktop doesn't have a "legacy" Start menu. A small cottage industry has grown up with registry hacks and lightweight programs to bring back the Start menu in the Developer Preview. Will Microsoft make it easy for admins and users to unlock the menu in the Consumer Preview?

What has changed beneath the Win8 covers When you're going through the Consumer Preview, be sure you check the new features with your current environment -- and sound off if you hit any snags. Here are some potential sticking points.

Virtualized storage -- called Storage Spaces in Windows 8 -- brings fully redundant backup and easily extensible disk pools to any Windows 8 client system with two or more hard disks. It's a brilliant concept, popularized in Windows Home Server's Drive Extender, now adapted for Windows 8 clients.

When the Consumer Preview arrives, you should spend time testing it with your corporate data backup routines. Although there shouldn't be any problems, it's a very new way of interacting with clients.

When the Consumer Preview arrives, you should spend time testing it with your corporate data backup routines. Although there shouldn't be any problems, it's a very new way of interacting with clients.

Much has been made of Windows 8's new refresh and reset capabilities -- analogous to a wipe command on a tablet or smartphone. Reset completely erases the client computer and reinstalls Windows.

Refresh is supposed to keep personal data and settings, retain Metro apps, and reinstall Windows. It isn't clear at this point precisely which personal data and settings are kept in a refresh -- and whether everything is obliterated in a reset. Make sure your apps survive.

Refresh is supposed to keep personal data and settings, retain Metro apps, and reinstall Windows. It isn't clear at this point precisely which personal data and settings are kept in a refresh -- and whether everything is obliterated in a reset. Make sure your apps survive.

All new PCs with the "Made for Windows 8" sticker must implement Secure Boot, a UEFI option that may bring you grief if you have users who need dual-boot capabilities.

Secure Boot enforces electronic signature checking on operating systems before they're loaded. Windows 8 will pass muster, but other OSes may not. Most -- but not necessarily all -- x86/x64 "Made for Windows 8" PCs will have an override capability. WOA devices will be able to boot only into Windows 8 Metro.

Secure Boot enforces electronic signature checking on operating systems before they're loaded. Windows 8 will pass muster, but other OSes may not. Most -- but not necessarily all -- x86/x64 "Made for Windows 8" PCs will have an override capability. WOA devices will be able to boot only into Windows 8 Metro.

The SkyDrive cloud storage service is due for a major makeover in the Consumer Preview, and part of the change involves single sign-on with a Windows Live ID. There are significant security implications as developers can "enable single sign-on and access a user's data on SkyDrive to make your Metro style app more personal -- with the user's consent, of course," as Microsoft puts it. Of course.

The Consumer Preview will give us the first glimpse of Microsoft's Windows Store. There's a particular twist here for the enterprise IT: The only way consumers can put Metro apps on their PCs and devices is through the Windows Store. (The only way WOA owners can put any apps at all -- or drivers -- on their devices is through the Windows Store.)

At the Build conference last September, Windows president Steve Sinofsky said that businesses would have a private area in the store, which would dish out corporate apps, but only to authorized machines. We haven't seen any details of exactly how that's going to work -- and it'll be an important question for all corporate developers.

At the Build conference last September, Windows president Steve Sinofsky said that businesses would have a private area in the store, which would dish out corporate apps, but only to authorized machines. We haven't seen any details of exactly how that's going to work -- and it'll be an important question for all corporate developers.

Microsoft has put us on notice that we'll see better and faster connections to Wi-Fi and other mobile networks, more adept power conservation, new and much more touch-friendly picture passwords, Windows to Go for running Windows 8 (presumably x86/x64) from a USB drive.

Some of those may apply to your shop. Hyper-V will be available on x86/x64 machines, but it isn't clear whether the Consumer Preview version is in any way different from the Developer Preview version in that regard.

Some of those may apply to your shop. Hyper-V will be available on x86/x64 machines, but it isn't clear whether the Consumer Preview version is in any way different from the Developer Preview version in that regard.

What the Windows 8 Consumer Preview means for IT From an IT point of view, the Consumer Preview should give you a very good idea of where your x86/x64-based applications will evolve in the near future on "legacy" PCs.

The Consumer Preview will also show you how Metro's going to work -- or how it won't work -- with WinRT-based apps you're thinking about developing. (WinRT is a new type of app using the Windows Runtime for portability between x86/x64 and ARM platforms.)

Microsoft continues to promise that WinRT apps will be transportable from the x86/x64 version of Windows 8 to WOA, so the strengths and weaknesses you see in Metro in the Consumer Preview edition should carry over to both x86/x64 and ARM platforms.

The Consumer Preview will also show you how Metro's going to work -- or how it won't work -- with WinRT-based apps you're thinking about developing. (WinRT is a new type of app using the Windows Runtime for portability between x86/x64 and ARM platforms.)

Microsoft continues to promise that WinRT apps will be transportable from the x86/x64 version of Windows 8 to WOA, so the strengths and weaknesses you see in Metro in the Consumer Preview edition should carry over to both x86/x64 and ARM platforms.

Sinofsky has stated, definitively, that the only applications allowed to run on the WOA desktop are four Office 15 apps -- Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and OneNote -- and a small handful of Microsoft apps, including Internet Explorer 10 and Windows File Manager. That's it. Per Sinofsky, "WOA does not support running, emulating, or porting existing [Win32s] x86/64 desktop apps." Period.

If you have hopes of developing an app that will run on cooler, lighter, cheaper, battery-miserly ARM devices, you'll have to write it Metro-style. Or if you can get it to run under Remote Desktop Services, it may be compatible with Internet Explorer 10 on a WOA device -- maybe.

The differences in Internet Explorer 10 between WOA and x86/x64 may drive your Web programmers nuts. IE10 runs on the Metro and desktop interfaces on both x86/x64 and WOA hardware. That's four different versions of IE10. Plug-ins won't work on three of the four combinations: They're banned on everything except the "legacy" version of IE10 running on x86/x64 hardware.

If your site requires a plug-in, and a user comes at the site using Metro on an x86/x64 PC, they'll be notified of the need for the plug-in and given a one-touch option to flip over to the legacy desktop version of IE10. But if the user has a WOA tablet, there's no option: They're dead in the water, like most other mobile users.

If your site requires a plug-in, and a user comes at the site using Metro on an x86/x64 PC, they'll be notified of the need for the plug-in and given a one-touch option to flip over to the legacy desktop version of IE10. But if the user has a WOA tablet, there's no option: They're dead in the water, like most other mobile users.

Which is probably just as well. No more Flash. No more PDF plug-ins. No more ActiveX. I'd be hard-pressed to say which of the three has led to more infected Windows PCs over the past decade.

One final note on testing: You're going to want a touch-enabled tablet to test Metro, even for the x86/x64-only Consumer Preview. Using touch is very, very different from mousing your way around. Although Windows 8 -- both Metro and the legacy environments -- will run on any monitor with a resolution of 1,024 by 768 pixels or higher, your PC must support 1,366-by-768 resolution or higher to get all Metro features to work.

In particular, if you want to use Windows Snap -- Microsoft's facility for helping apps run side by side -- to get a Metro window and a second window displayed next to one another, you need 1,366-by-768 resolution or better. Quoting Sinofsky again: "The resolution that supports all the features of Windows 8, including multitasking with Snap is 1,366 by 768.

We chose this resolution as it can fit the width of a snapped app, which is 320 pixels (also the width designed for many phone layouts), next to a main app at 1,024-by-768 app (a common size designed for use on the Web)."

We chose this resolution as it can fit the width of a snapped app, which is 320 pixels (also the width designed for many phone layouts), next to a main app at 1,024-by-768 app (a common size designed for use on the Web)."

Beyond the Windows 8 Consumer Preview: The great unknown Over the past year we've gone through layers and layers of rumors, particularly about Windows 8 on ARM. Features come and go. Perhaps the most egregious example is in a video made at the Build conference last September. It shows Roger Gulrajani, from the Windows Hardware Ecosystem group, demonstrating Flash running in IE10, on the desktop, on an ARM device.

Now, we're assured IE10 won't run Flash on ARM devices. That much has changed in just four months. Or maybe Microsoft itself was confused and got it wrong; there were several such misstatements at Build, and you can expect confusion to continue given the addition of ARM support for just part of the complete Windows 8 experience.

Now, we're assured IE10 won't run Flash on ARM devices. That much has changed in just four months. Or maybe Microsoft itself was confused and got it wrong; there were several such misstatements at Build, and you can expect confusion to continue given the addition of ARM support for just part of the complete Windows 8 experience.

And I haven't even touched on Office 15. We know very little about it, except Sinofsky has promised, "WOA includes desktop versions of the new Microsoft Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and OneNote. These new Office applications, code-named 'Office 15,' have been significantly architected for both touch and minimized power/resource consumption, while also being fully featured for consumers and providing complete document compatibility."

Will all WOA devices ship with Office 15? If so, as full versions or ad-supported giveaways? At an extra cost or free? For that matter, will x86/x64 Windows 8 PCs ship with Office 15, or a stunted relative? I Dunno You Tell Me!?

ASUS CM1740-US-2AG Desktop Repair Guide

What you can get for $500 keeps getting better and better every year and the ASUS CM1740-US-2AG is certainly a nice step up from the model just six months ago.

This is a good all around system thanks to its quad core AMD processor, 8GB of memory, dedicated graphics and wireless networking.

It may not be as fast as an Intel based desktop at this price range but it still provides more than enough for the average user.

The one downside is that the power supply does limit the potential to upgrade the graphics even further for those looking to get a low cost gaming setup.

Pros

Dedicated Graphics Card

8GB Memory

Wireless Networking

Cons

Processor Slower Than Many Dual Core Intel Based Systems

Low Wattage Power Supply Limits Graphics Upgrades

Description

AMD A8-3820 Quad Core Desktop Processor

8GB PC3-128000 DDR3 Memory

1TB 7200rpm SATA Hard Drive

24x DVD+/-RW Dual Layer Burner

AMD Radeon HD 7470 Dedicated Graphics Card With 1GB Memory

5.1 Audio Suuport

Gigabit Ethernet, 802.11b/g/n Wireless

Two USB 3.0, Six USB 2.0, HDMI, DVI, VGA, 6-in-1 Card Reader

Windows 7 Home Premium, Office Starter

Review - ASUS CM1740-US-2AG

Aug 20 2012 - The ASUS CM1740-US-2AG is extremely similar to the CM1720-US-2AF that I reviewed six months ago. It uses the same base components with a few minor upgrades. The processor has been upgraded from the AMD Fusion A6-3620 quad core processor to a slightly faster A8-3820 quad core processor.

In addition to the processor, the memory was upgraded for 4 to 8GB of DDR3. This is one of the largest capacities you will see in this price range and provides it with the extra boost it needs for dealing with multiasking which is one of the key benefits from the four cores. There are even four memory slots so the RAM can be upgraded further if needed. It should be noted though that in many tasks, the A8 processors still falls behind many of the Intel dual-core processors. Still, for the average user, this should provide it with more than enough performance for the web browsing, media viewing and productivity software.

Storage features for the ASUS CM1740-US-2AG remain unchanged from the 2AF model I looked at six months ago. It features a one terabyte hard drive that provides it with a large amount of space for applications, data and media files. This is typical now for most desktop in this price range. The drive does spin at the full 7200rpm spin rate which does give it a slight speed advantage over those that use the green class drives. If you need addition space, there are two USB 3.0 ports available for use with high speed external hard drives. This was pretty unique six months ago but many more computers now features these ports. A standard dual layer DVD burner is included for playback and recording for CD or DVD media.

The big difference between this system and the last model I reviewed is the graphics system. The AMD A8 processor does feature an integrated Radeon HD 6550D which is a very good system that offers some decent 3D performance and a step up from what the A6 had. What ASUS has done though is include a dedicated AMD Radeon HD 7470 graphics card. This is still a relatively low end graphics card that won't do much beyond basic 3D but it does have the ability to run in a CrossFire setup with the internal graphics to offer even better 3D performance.

Now, it isn't going to be as good as a midrange card and it does have its quirk in certain programs. This also offers improved acceleration for non-3D applications which is becoming more useful. The graphics card can be swapped out for a higher model but it is still restricted by the relatively low 300 watt power supply.

For those that already have a wireless network setup in their home for use with mobile devices, the CM1740-US-2AG does come with a 802.11b/g/n wireless networking adapter. This makes it easy to setup the system without needing to stretch an ethernet cable between the desktop and your broadband connection.

In terms of the competition for ASUS, the closest desktop system in the $500 price range would be the Acer Aspire AM3450-UR10P. That system offers an eight core processor for additional performance but comes with less memory. While it also features a dedicated graphics card, it falls short of this ASUS system with its newer 7000 series card and the ability to work with the integrated graphics core.

Thursday, November 8, 2012

My HP Pavilion DM1-4010EZ Installing Linux Mint 12 Experience

When we last left off working on our lovely new HP DM1-4010EX Sub Notebook, I had just finished installing and configuring Microsoft Windows 7 Home Premium.

Now with the windows operating system out of the way it is time to move into installing a real computer operating system on it, and for the sake of variety the choice this time will be Linux Mint 12 and Cinnamon 1.1.3.

The very first thing to do is prepare the internal hard disk drive. As I said in the previous post, all four of the Primary Partitions are used in the default configuration of this system.

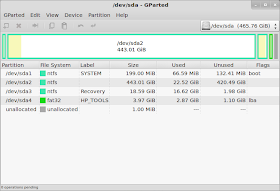

The disk layout looks like this in GParted:

Now with the windows operating system out of the way it is time to move into installing a real computer operating system on it, and for the sake of variety the choice this time will be Linux Mint 12 and Cinnamon 1.1.3.

The very first thing to do is prepare the internal hard disk drive. As I said in the previous post, all four of the Primary Partitions are used in the default configuration of this system.

The disk layout looks like this in GParted:

So there is a tiny bootloader partition, a huge Windows C: partition, a small Windows Recovery partition, and a very small HP Tools partition. One of them has got to go, because the antiquated MBR disk labeling/management system can not have more than four partitions.

I will say this one more time... Make Sure You Have Created A Set Of Recovery DVDs. Once you delete the Recovery partition, you will never have another chance to create them.

The other consequence of deleting the Recovery partition is that you can not do the F11-Recovery procedure, if you ever really need to restore Windows you will have to do it from the DVDs.

I will say this one more time... Make Sure You Have Created A Set Of Recovery DVDs. Once you delete the Recovery partition, you will never have another chance to create them.

The other consequence of deleting the Recovery partition is that you can not do the F11-Recovery procedure, if you ever really need to restore Windows you will have to do it from the DVDs.

Now we are ready to delete a partition. The obvious candidate is the Recovery partition, both because of its size and content (we know we have it copied on DVD).

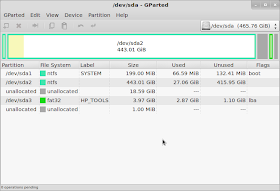

The simplest and most direct thing to do is to delete it in GParted, since we already have that running. But in this case it is probably better to go back to Windows and delete it using the HP Recovery Manager, so that it knows that the partition is gone. Either way you do it, once the partition has been deleted the disk will look like this in GParted:

The simplest and most direct thing to do is to delete it in GParted, since we already have that running. But in this case it is probably better to go back to Windows and delete it using the HP Recovery Manager, so that it knows that the partition is gone. Either way you do it, once the partition has been deleted the disk will look like this in GParted:

Although it is quite small, that is actually enough free space to load Linux - especially if you are only "sticking your toes in the water" at this point, and want to see how it goes.

If you want more space you can just shrink the Windows partition (/dev/sda2). The next step is to create an Extended partition in the free space, and then either create two more logical partitions within that for the Linux root and swap, or just leave the extended partition empty and let the Linux installer create the partitions it wants.

If you want more space you can just shrink the Windows partition (/dev/sda2). The next step is to create an Extended partition in the free space, and then either create two more logical partitions within that for the Linux root and swap, or just leave the extended partition empty and let the Linux installer create the partitions it wants.

It's finally time to actually install Linux Mint 12.

Download the ISO image from the Linux Mint Downloads page. I just about always use the 64-bit images now, but of course you can still use 32-bit if you want or need to, or if you are just extremely conservative. The ISO image can be converted to a bootable USB stick using the "Startup Disk Creator" utility on any running Mint 9/10/11 system, or of course it can be burned to a DVD-R (sorry, too big for CD-R).

Insert the USB stick or connect the USB DVD drive, turn on power and press F9 (the boot device selection key for HP systems). When booting from USB stick, it still stops with an error about the vesamenu not being a COM32R image, and then says "boot: ". Sigh.

I wish this didn't happen, because it confuses an awful lot of inexperienced users. All you have to do is type "live" and press return, but figuring that out can be daunting. I haven't tried burning a DVD for Mint in a long time, does this still happen when booting that way as well?

Download the ISO image from the Linux Mint Downloads page. I just about always use the 64-bit images now, but of course you can still use 32-bit if you want or need to, or if you are just extremely conservative. The ISO image can be converted to a bootable USB stick using the "Startup Disk Creator" utility on any running Mint 9/10/11 system, or of course it can be burned to a DVD-R (sorry, too big for CD-R).

Insert the USB stick or connect the USB DVD drive, turn on power and press F9 (the boot device selection key for HP systems). When booting from USB stick, it still stops with an error about the vesamenu not being a COM32R image, and then says "boot: ". Sigh.

I wish this didn't happen, because it confuses an awful lot of inexperienced users. All you have to do is type "live" and press return, but figuring that out can be daunting. I haven't tried burning a DVD for Mint in a long time, does this still happen when booting that way as well?

The Mint Live system then comes up, and you will be presented with a normal Mint 12 desktop. One of the icons on that desktop is "Install Linux Mint", which gets you to the Mint installer (duh). The first installer screen asks for the language, which will be used for this installation dialog and as the default for the installed system.

The next screen informs you of the status of disk space, power and Internet connection. You can do the installation just fine without an internet connection, but you really should have power connected, or at least be sure that the battery is full when you start. It's not much fun to have the system die halfway through the installation.

Next you get a chance to connect to a wireless network. This is useful if you want to install updates or additional packages during installation, but as I said it is not absolutely necessary, and I seldom bother with it.

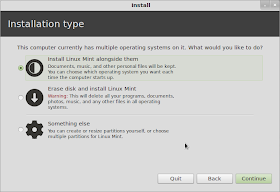

Now comes "Installation Type", which is where you define the disk allocation. If you just created an Extended Partition and left it empty, you can leave this on "Install Linux Mint Alongside Them" and it will do what is necessary. If you like to control things, you can choose "Something Else", which is what I typically do. If you want to ditch Windows and have only Linux installed, choose "Erase disk...".

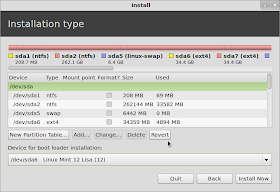

Next you can decide if you want to use the Windows bootloader or Linux GRUB. At the bottom of the window, if you leave the Device for bootloader installation on its default (which is the MBR of the hard drive), you will get Linux GRUB for a bootloader, with Windows listed as a boot option. If you change this to put the bootloader in the root partition of the installed system, you will still have the Windows bootloader, and you will have to follow the instructions I posted a while back to configure that to multi-boot Linux as well.

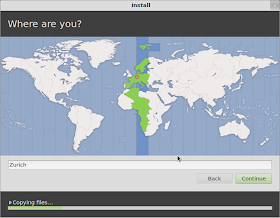

At this point the installer will actually split off and start doing the installation in the background while it continues to ask you a few more questions about the configuration. First is your time zone:

Then comes the keyboard layout...

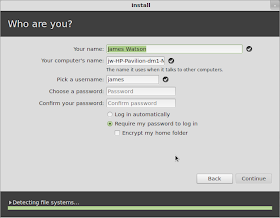

Then comes a series of screens for the the user information.

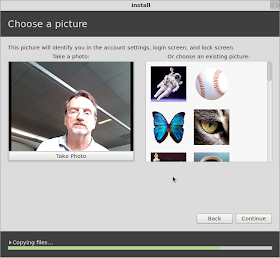

You get to choose a picture for your account - if there is anyone here who really feels that whatever random picture might be taken by the webcam while you are installing is something you might like to have on your account permanently... well, congratulations, you are doing better than I am...

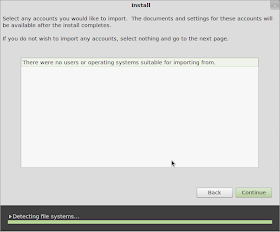

If there is anything else already on the disk that the Installer recognizes and might take over user account information from, it comes up in the next screen.

Once you have gotten this far, you will get some entertaining propaganda screens while the installation finishes. Hooray! When the installation finishes, reboot (and configure the Windows bootloader if you need to), and you'll be up and running Linux Mint 12.

That might seem like quite a long process, but each of those steps only takes a short time, and the entire installation can be done in 30 minutes if you are reading everything very carefully and thinking about the answers, or as little as 15 minutes or less once you are familiar with it and you're doing it on "autopilot".

Now comes the good news - it works! As far as I can tell, with one small exception, everything works very nicely. Screen resolution is correct (1366x768), wired and wireless networking are ok (although the signal strength looks weak, as it did under Windows), the touchpad works just fine (SO much better for my nerves than the ClickPad), the Fn-keys for brightness, audio and WiFi control, Suspend/Resume (and it does each of those in less than 5 seconds), Mobile Broadband with my Huawei USB dongle... the only thing I have noticed which doesn't work is Bluetooth.

This is a bit of an inconvenience for me, because I sometimes use a bluetooth mouse or printer, but it is certainly not a big deal. By the way, in addition to showing the default Mint 12 desktop, I'll include the simplest way to tell if Bluetooth is working. It seems to me that the Bluetooth icon used to not show up in the panel if Bluetooth wasn't actually available, but now it looks like it is always there - perhaps this is something new with Gnome 3, I haven't really cared enough to look into it yet.

But if Bluetooth is actually available and working, when you click on the Bluetooth icon you will get options for "Send files to device..." and "Set up new device...". If you don't see those, as in the screen below, then Bluetooth is not available, so don't waste a lot of time tearing your hair out trying to figure out how to add a Bluetooth device, as I did, when Bluetooth isn't working at all.

I expect this problem to be taken care of by an update in the near future.

This is a bit of an inconvenience for me, because I sometimes use a bluetooth mouse or printer, but it is certainly not a big deal. By the way, in addition to showing the default Mint 12 desktop, I'll include the simplest way to tell if Bluetooth is working. It seems to me that the Bluetooth icon used to not show up in the panel if Bluetooth wasn't actually available, but now it looks like it is always there - perhaps this is something new with Gnome 3, I haven't really cared enough to look into it yet.

But if Bluetooth is actually available and working, when you click on the Bluetooth icon you will get options for "Send files to device..." and "Set up new device...". If you don't see those, as in the screen below, then Bluetooth is not available, so don't waste a lot of time tearing your hair out trying to figure out how to add a Bluetooth device, as I did, when Bluetooth isn't working at all.

I expect this problem to be taken care of by an update in the near future.

So, there you have it. I hope all of the detail was worthwhile - I'm certainly not going to be doing this on a regular basis, but I really wanted to show that installing Linux, whether it be openSuSE, Mint, or any of the other popular distributions, was not black magic, and really wasn't even all that difficult or dangerous.

What we have ended up with here is a very nice sub-notebook, it looks good, feels good, works well, and when we turn it on we can choose whether to run Linux Mint 12 (loud cheers in the background) or Windows 7 Home Premium (boos and hisses, and I am ducking lemons and rotten tomatoes being thrown from the cheap seats).

What we have ended up with here is a very nice sub-notebook, it looks good, feels good, works well, and when we turn it on we can choose whether to run Linux Mint 12 (loud cheers in the background) or Windows 7 Home Premium (boos and hisses, and I am ducking lemons and rotten tomatoes being thrown from the cheap seats).

Next on the agenda: add the Cinnamon desktop, and compare it to Gnome and MGSE.

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

Lighthouse Security Group Expands Operations to Support its Proven Cloud

Lighthouse Security Group Expands Operations to Support its Proven Cloud Alternative to Traditional Identity and Access Management Systems

Company sales, marketing and product expansion to support continued success of Lighthouse Gateway™ cloud-based IAM platform

February 15, 2012 09:03 AM Eastern Time

LINCOLN, R.I.--(EON: Enhanced Online News)--Led by cloud-based identity and access management (IAM) pioneer Eric Maass, Lighthouse Security Group today announced expanded operations to support the launch of the next generation of its Lighthouse Gateway™ platform.

“We are ramping up across all functional areas to support the continued success of Lighthouse Gateway”

Based on the IAM platform that Maass designed and deployed for the U.S. Air Force, Lighthouse Gateway is a secure, cloud-based IAM platform that helps reduce the risk, cost and complexity typically associated with traditional on-premise infrastructure. The Gateway combines the best of both worlds, with a foundation based on proven IAM technology from IBM, surrounded by nearly a million lines of proprietary code that optimize it for the cloud and make it extremely easy to manage and deploy.

“We are ramping up across all functional areas to support the continued success of Lighthouse Gateway,” said Maass, CTO, Lighthouse Security Group. “With its proven technology, quick deployment time and reduced total cost of ownership, Lighthouse Gateway has been an efficient and cost-effective cloud-based alternative to traditional IAM systems since day one.

Additionally, in recent years we’ve performed extensive research and development and worked closely with our customers to integrate cutting-edge security and compliance features. We are supporting our product expansion with increased investments in sales and marketing to drive increased awareness of our time-tested, best-of-breed IAM platform.”

Lighthouse Gateway has already been adopted and deployed by companies such as Molson Coors Brewing Company and VantisLife Insurance Company, and has received accolades from several industry analyst firms and publications – and has been recognized by IBM – for the innovation and demonstrated business value its platform brings to the IAM market. The next generation of the Lighthouse Gateway now includes several new features that bolster its security and compliance capabilities.

Military Heritage Results in Proven IAM Solution

Lighthouse Security Group, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lighthouse Computer Services, Inc., has a deep military heritage and boasts an industry-leading team of IAM and cloud computing experts.

Prior to joining Lighthouse Security Group, Maass was the chief security architect for the U.S. Air Force’s Global Combat Support System (GCSS-AF), where he was responsible for the architecture and design of the GCSS-AF’s net-centric IAM infrastructure – a precursor to what is typically referred to today as “cloud computing.”

Realizing the cloud’s potential to deliver enterprise-class IAM capabilities at a price point companies of all sizes can afford, Maass and several of his colleagues joined Lighthouse Security Group to commercialize the technology through the Lighthouse Gateway platform. A culmination of the team’s nearly seven years of experience working with the U.S. Air Force, Lighthouse Gateway is built with military-grade infrastructure and leverages a security model that has been proven within one of the world’s most demanding IT infrastructures – making it one of the most secure IAM platforms available.

“Lighthouse Security Group presented me with a unique opportunity,” Maass commented. “I was able to take the IAM technology I developed for the U.S. Air Force and create a new, yet battle-tested, solution that was tailored to enterprise environments. The military and other government agencies are often on the front lines of the fight against cyber attacks, so the lessons learned and insights gained with the U.S. Air Force have enabled us to build a solution that leapfrogs all others in the market.”

For more information about Lighthouse Gateway and the advantages of cloud-based identity and access management, visit www.DiscoverLighthouseGateway.com.

About Lighthouse Security Group, LLC

Lighthouse Security Group, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lighthouse Computer Services, Inc., is a premier provider of cloud-based Identity and Access Management (IAM) services. Founded in 2007, the company serves clients throughout Financial Services, Healthcare, Retail, Manufacturing, Higher Education, and the Department of Defense. With an engineering heritage rooted in both IBM and defense-technology leader Lockheed Martin, Lighthouse Security Group is home to a team that comprises industry authorities, patent-holding innovators and world-class IAM talent. The company’s major operations include its market-leading Lighthouse Gateway cloud IAM offering, commercial systems integration services and information security services for the U.S. Department of Defense.

Company sales, marketing and product expansion to support continued success of Lighthouse Gateway™ cloud-based IAM platform

February 15, 2012 09:03 AM Eastern Time

LINCOLN, R.I.--(EON: Enhanced Online News)--Led by cloud-based identity and access management (IAM) pioneer Eric Maass, Lighthouse Security Group today announced expanded operations to support the launch of the next generation of its Lighthouse Gateway™ platform.

“We are ramping up across all functional areas to support the continued success of Lighthouse Gateway”

Based on the IAM platform that Maass designed and deployed for the U.S. Air Force, Lighthouse Gateway is a secure, cloud-based IAM platform that helps reduce the risk, cost and complexity typically associated with traditional on-premise infrastructure. The Gateway combines the best of both worlds, with a foundation based on proven IAM technology from IBM, surrounded by nearly a million lines of proprietary code that optimize it for the cloud and make it extremely easy to manage and deploy.

“We are ramping up across all functional areas to support the continued success of Lighthouse Gateway,” said Maass, CTO, Lighthouse Security Group. “With its proven technology, quick deployment time and reduced total cost of ownership, Lighthouse Gateway has been an efficient and cost-effective cloud-based alternative to traditional IAM systems since day one.

Additionally, in recent years we’ve performed extensive research and development and worked closely with our customers to integrate cutting-edge security and compliance features. We are supporting our product expansion with increased investments in sales and marketing to drive increased awareness of our time-tested, best-of-breed IAM platform.”

Lighthouse Gateway has already been adopted and deployed by companies such as Molson Coors Brewing Company and VantisLife Insurance Company, and has received accolades from several industry analyst firms and publications – and has been recognized by IBM – for the innovation and demonstrated business value its platform brings to the IAM market. The next generation of the Lighthouse Gateway now includes several new features that bolster its security and compliance capabilities.

Military Heritage Results in Proven IAM Solution

Lighthouse Security Group, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lighthouse Computer Services, Inc., has a deep military heritage and boasts an industry-leading team of IAM and cloud computing experts.

Prior to joining Lighthouse Security Group, Maass was the chief security architect for the U.S. Air Force’s Global Combat Support System (GCSS-AF), where he was responsible for the architecture and design of the GCSS-AF’s net-centric IAM infrastructure – a precursor to what is typically referred to today as “cloud computing.”

Realizing the cloud’s potential to deliver enterprise-class IAM capabilities at a price point companies of all sizes can afford, Maass and several of his colleagues joined Lighthouse Security Group to commercialize the technology through the Lighthouse Gateway platform. A culmination of the team’s nearly seven years of experience working with the U.S. Air Force, Lighthouse Gateway is built with military-grade infrastructure and leverages a security model that has been proven within one of the world’s most demanding IT infrastructures – making it one of the most secure IAM platforms available.

“Lighthouse Security Group presented me with a unique opportunity,” Maass commented. “I was able to take the IAM technology I developed for the U.S. Air Force and create a new, yet battle-tested, solution that was tailored to enterprise environments. The military and other government agencies are often on the front lines of the fight against cyber attacks, so the lessons learned and insights gained with the U.S. Air Force have enabled us to build a solution that leapfrogs all others in the market.”

For more information about Lighthouse Gateway and the advantages of cloud-based identity and access management, visit www.DiscoverLighthouseGateway.com.

About Lighthouse Security Group, LLC

Lighthouse Security Group, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lighthouse Computer Services, Inc., is a premier provider of cloud-based Identity and Access Management (IAM) services. Founded in 2007, the company serves clients throughout Financial Services, Healthcare, Retail, Manufacturing, Higher Education, and the Department of Defense. With an engineering heritage rooted in both IBM and defense-technology leader Lockheed Martin, Lighthouse Security Group is home to a team that comprises industry authorities, patent-holding innovators and world-class IAM talent. The company’s major operations include its market-leading Lighthouse Gateway cloud IAM offering, commercial systems integration services and information security services for the U.S. Department of Defense.

Sync Your Data without the Cloud - Technology Review

Sync Your Data without the Cloud And Making Your Computing Experience Easier!

New software lets you rouse a sleeping PC to retrieve data remotely.

Files on a home computer system could soon be accessible from anywhere in the world over the internet, even when the computer holding them is switched off, thanks to a prototype file-synching system developed at Microsoft's research labs.

The system is designed to demonstrate an alternative to a growing array of cloud services. "One of our underlying principles is that you don't always want to put all of your data in the cloud and give it to Google or some other corporation," said Michelle Mazurek, of Carnegie Mellon University, presenting the technology at the Usenix File and Storage Technology conference in San Jose, California, last week.

Cloud computing systems can synchronize data between computers to provide access from anywhere, but users have to plan in advance which data they want to sync, and they have to trust a third party with their files so be sure to encrypt them first before storing them in the cloud incase the cloud is compromised. It happens. You've Been Warned.

Mazurek and researchers at Microsoft's labs in Cambridge, U.K., built an alternative in the form of a simple application that makes all the data on one of a person's computers visible and accessible from any of their others. The user's devices act as personal cloud servers, and the software, called ZZFS, uses a novel hardware trick to wake up desktop and laptop computers that are in standby or sleep mode. This means that a file left on a closed laptop sitting on the couch at home can be retrieved from work.

A user can use the Windows Explorer file browser to see all the files and folders on other computers with ZZFS installed. Applications like Microsoft Office and iTunes can open those files normally, once they have been retrieved over the Internet.

A piece of hardware called Somniloquy is the reason this system works. The USB device, which acts like a smarter version of an ordinary network card that connects a computer to the Internet, can wake a sleeping computer and retrieve data from it before powering it back down. It has its own low-power processor and a few gigabytes of storage to cache files sent its way while a computer wakes up.

Mazurek believes that the overall design of ZZFS can be more accommodating of the spontaneous—some might say disorganized—way most people manage data spread across many devices. "Users don't always know or plan what they need to have ahead of time," she said, alluding to the fact that cloud services cannot sync all of a person's data, so users must choose what is backed up

New software lets you rouse a sleeping PC to retrieve data remotely.

Files on a home computer system could soon be accessible from anywhere in the world over the internet, even when the computer holding them is switched off, thanks to a prototype file-synching system developed at Microsoft's research labs.

The system is designed to demonstrate an alternative to a growing array of cloud services. "One of our underlying principles is that you don't always want to put all of your data in the cloud and give it to Google or some other corporation," said Michelle Mazurek, of Carnegie Mellon University, presenting the technology at the Usenix File and Storage Technology conference in San Jose, California, last week.

Cloud computing systems can synchronize data between computers to provide access from anywhere, but users have to plan in advance which data they want to sync, and they have to trust a third party with their files so be sure to encrypt them first before storing them in the cloud incase the cloud is compromised. It happens. You've Been Warned.

Mazurek and researchers at Microsoft's labs in Cambridge, U.K., built an alternative in the form of a simple application that makes all the data on one of a person's computers visible and accessible from any of their others. The user's devices act as personal cloud servers, and the software, called ZZFS, uses a novel hardware trick to wake up desktop and laptop computers that are in standby or sleep mode. This means that a file left on a closed laptop sitting on the couch at home can be retrieved from work.

A user can use the Windows Explorer file browser to see all the files and folders on other computers with ZZFS installed. Applications like Microsoft Office and iTunes can open those files normally, once they have been retrieved over the Internet.

A piece of hardware called Somniloquy is the reason this system works. The USB device, which acts like a smarter version of an ordinary network card that connects a computer to the Internet, can wake a sleeping computer and retrieve data from it before powering it back down. It has its own low-power processor and a few gigabytes of storage to cache files sent its way while a computer wakes up.

Mazurek believes that the overall design of ZZFS can be more accommodating of the spontaneous—some might say disorganized—way most people manage data spread across many devices. "Users don't always know or plan what they need to have ahead of time," she said, alluding to the fact that cloud services cannot sync all of a person's data, so users must choose what is backed up

Incontro e vademecum per navigare sicuri in internet

Come proteggere i propri dati personali navigando in internet? Come avvalersi dei benefici dello shopping on line senza correre rischi? Come tutelare i bambini davanti al computer?

A queste domande risponderà mercoledì 22 febbraio alle 21 all’auditorium Marco Biagi (largo Biagi 2) Michele Colajanni, docente al Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’informazione dell’Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia e direttore del Centro di ricerca interdipartimentale sulla sicurezza. L’esperto, che interverrà su “Sicurezza informatica e protezione delle persone” nell’ambito di un mini ciclo promosso dalle biblioteche del Comune di Modena e dall’Università, anticipa alcuni temi dell’incontro proponendo un utile vademecum al quale attenersi.

Acquisti. Quando si fanno acquisti on line, è necessario controllare di trovarsi in una connessione “https” e non “http”. Si può controllare nella barra dell’indirizzo. In genere, sul browser appare il simbolo di un lucchetto giallo in basso. Meglio utilizzare solo i siti web di aziende note e chiedere alla banca di inviarci un sms a ogni utilizzo della carta di credito.

Antivirus. Le tecnologie per la sicurezza aiutano, ma non risolvono tutti i problemi. É importante avere un antivirus e attivare gli aggiornamenti automatici. Ce ne sono di gratuiti (Clamav, Avg, Avast, Avira, Comodo), ma spendere 40 euro per una versione commerciale e’ un buon investimento.

Filtri. I filtri sono in grado di proteggere la navigazione dei bambini in rete fino alla terza elementare. I ragazzi più grandi sono in grado di superare tutte le barriere, anche perché hanno molteplici punti di accesso, come i cellulari o i computer degli amici. La sicurezza dei ragazzi si gioca sul piano educativo più che su quello tecnologico.

Lavoro. Sarebbe opportuno non utilizzare il computer di lavoro per scopi privati.

Link, allegati e software. Prima di cliccare su un link o aprire un allegato di posta elettronica, è meglio farsi alcune domande: conosciamo il mittente? se lo conosciamo, è plausibile che ci abbia inviato quel testo? Se si hanno dubbi, anche minimi, si può telefonare al presunto mittente per verificare. Meglio non installare software di dubbia provenienza.

Password. Una password sicura è fatta di almeno 8 caratteri, non è una parola che si trova sul dizionario, non è un nome proprio. Possibilmente, dovrebbe contenere sia caratteri maiuscoli sia minuscoli, almeno un numero e un carattere speciale (punteggiatura, barre, trattini, eccetera). La password non si deve mai scrivere in prossimità del computer.

Posta elettronica e social network. Sono i punti di contatto dall’esterno verso di noi e vanno presidiati con attenzione. Le credenziali (username e password) non si devono cedere a nessuno ed è importante fare sempre il log out al termine di ogni sessione. Sui social network è bene non dare la propria “amicizia” a chicchessia: gli utenti sono 800 milioni al mondo e tra essi si nascondono anche criminali e truffatori.

Truffe. Ci sono alcuni tipi di trappole molto comuni: presunte vittorie a lotterie di cui non si è comprato il biglietto, offerte di lavoro via mail, proposte di affari da sconosciuti, richieste di contatto da donne meravigliose. Secondo i dati rilevati dalla Norton, una delle principali aziende produttrici di antivirus, il valore dei reati legati al “cybercrime” è stimato in 388 miliardi di euro l’anno (114 miliardi di perdite dirette, 274 di risorse e tempo impiegati nelle indagini), una cifra che a livello globale è paragonabile al valore dei traffici internazionali di droga (400 miliardi di euro l’anno). Gli autori di crimini informatici, infatti, non sono più gli “hacker” singoli, ma gruppi di professionisti legati alla grande criminalità organizzata e allo spionaggio industriale.

Il ciclo “Uomini e computer: la nuova alleanza” è realizzato grazie al contributo della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Modena, e continuerà lunedì 5 marzo con “Benvenuto amico robot”, un incontro dedicato ai modelli di intelligenze artificiali bioispirate. Il relatore sarà Dario Floreano, direttore del Laboratorio di sistemi intelligenti (LIS) del Politecnico di Losanna. I suoi interessi di ricerca si focalizzano sulla robotica biomimetica e sull’intelligenza artificiale.

A queste domande risponderà mercoledì 22 febbraio alle 21 all’auditorium Marco Biagi (largo Biagi 2) Michele Colajanni, docente al Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’informazione dell’Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia e direttore del Centro di ricerca interdipartimentale sulla sicurezza. L’esperto, che interverrà su “Sicurezza informatica e protezione delle persone” nell’ambito di un mini ciclo promosso dalle biblioteche del Comune di Modena e dall’Università, anticipa alcuni temi dell’incontro proponendo un utile vademecum al quale attenersi.

Acquisti. Quando si fanno acquisti on line, è necessario controllare di trovarsi in una connessione “https” e non “http”. Si può controllare nella barra dell’indirizzo. In genere, sul browser appare il simbolo di un lucchetto giallo in basso. Meglio utilizzare solo i siti web di aziende note e chiedere alla banca di inviarci un sms a ogni utilizzo della carta di credito.

Antivirus. Le tecnologie per la sicurezza aiutano, ma non risolvono tutti i problemi. É importante avere un antivirus e attivare gli aggiornamenti automatici. Ce ne sono di gratuiti (Clamav, Avg, Avast, Avira, Comodo), ma spendere 40 euro per una versione commerciale e’ un buon investimento.

Filtri. I filtri sono in grado di proteggere la navigazione dei bambini in rete fino alla terza elementare. I ragazzi più grandi sono in grado di superare tutte le barriere, anche perché hanno molteplici punti di accesso, come i cellulari o i computer degli amici. La sicurezza dei ragazzi si gioca sul piano educativo più che su quello tecnologico.

Lavoro. Sarebbe opportuno non utilizzare il computer di lavoro per scopi privati.

Link, allegati e software. Prima di cliccare su un link o aprire un allegato di posta elettronica, è meglio farsi alcune domande: conosciamo il mittente? se lo conosciamo, è plausibile che ci abbia inviato quel testo? Se si hanno dubbi, anche minimi, si può telefonare al presunto mittente per verificare. Meglio non installare software di dubbia provenienza.

Password. Una password sicura è fatta di almeno 8 caratteri, non è una parola che si trova sul dizionario, non è un nome proprio. Possibilmente, dovrebbe contenere sia caratteri maiuscoli sia minuscoli, almeno un numero e un carattere speciale (punteggiatura, barre, trattini, eccetera). La password non si deve mai scrivere in prossimità del computer.

Posta elettronica e social network. Sono i punti di contatto dall’esterno verso di noi e vanno presidiati con attenzione. Le credenziali (username e password) non si devono cedere a nessuno ed è importante fare sempre il log out al termine di ogni sessione. Sui social network è bene non dare la propria “amicizia” a chicchessia: gli utenti sono 800 milioni al mondo e tra essi si nascondono anche criminali e truffatori.

Truffe. Ci sono alcuni tipi di trappole molto comuni: presunte vittorie a lotterie di cui non si è comprato il biglietto, offerte di lavoro via mail, proposte di affari da sconosciuti, richieste di contatto da donne meravigliose. Secondo i dati rilevati dalla Norton, una delle principali aziende produttrici di antivirus, il valore dei reati legati al “cybercrime” è stimato in 388 miliardi di euro l’anno (114 miliardi di perdite dirette, 274 di risorse e tempo impiegati nelle indagini), una cifra che a livello globale è paragonabile al valore dei traffici internazionali di droga (400 miliardi di euro l’anno). Gli autori di crimini informatici, infatti, non sono più gli “hacker” singoli, ma gruppi di professionisti legati alla grande criminalità organizzata e allo spionaggio industriale.

Il ciclo “Uomini e computer: la nuova alleanza” è realizzato grazie al contributo della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Modena, e continuerà lunedì 5 marzo con “Benvenuto amico robot”, un incontro dedicato ai modelli di intelligenze artificiali bioispirate. Il relatore sarà Dario Floreano, direttore del Laboratorio di sistemi intelligenti (LIS) del Politecnico di Losanna. I suoi interessi di ricerca si focalizzano sulla robotica biomimetica e sull’intelligenza artificiale.

How Companies Are 'Defining Your Worth' Online Now

One of the fastest-growing online businesses is the business of spying on Internet users. Using sophisticated software that tracks people's online movements through the Web, companies collect the information and sell it to advertisers.

Every time you click a link, fill out a form or visit a website, advertisers are working to collect personal information about you, says Joseph Turow, a professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. They then target ads to you based on that information.

On Wednesday's Fresh Air, Turow — the author of the book The Daily You: How the New Advertising Industry is Defining Your Identity and Your Worth -- details how companies are tracking people through their computers and cellphones in order to personalize the ads they see.

Turow tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross that tracking is ubiquitous across the Internet, from search engines to online retailers and even greeting card companies. A recent Valentine's Day card sent to his wife, for instance, contained trackers from 15 separate companies.

"[Advertisers] might make inferences about me and romance, they might make inferences — right or wrong — about my age, they might know where I did this — because of some sense of where my computer is, my IP address," he says. "There are a lot of things they can infer about me even from [a greeting card]."

But advertisers are not just limited to tracking your Internet browsing, says Turow. They're also trying to connect what you do on phones and other mobile devices, which are typically tied to an individual user and account.

"In the holy grail vision of this," says Turow, "the idea of what you do on mobile should be connected to what you do on the Internet, and what you do on the Internet should be connected to what you do on your iPad, and eventually all of this will converge on what you watch on television."

But right now, says Turow, advertisers are still in the beginning stages of tracking users. He says he still receives ads for dating sites — despite being happily married.

"We're at the beginning of this new world," he says. "It's like the beginning of the airplane industry. Things screw up, and yet we have to look down the line because we're going to have Boeing 747s down the way."

Using The Social Space To Market Ads

Google is a leading innovator in the advertising world. Turow explains how the search engine makes money through online ads in search results as well as through contextual display advertisements (aka banner ads) located on various websites.

"Increasingly, Google uses information they've collected about you to determine which ads to show you," he says. "Recently Google announced they're going to merge all of their properties — and everything they have about you with almost all of their properties — so they will use what they know about you through Gmail, through regular Google search and through other Google properties to figure out what ads to show you."

Facebook also uses what you like on its site to target ads, says Turow, but it's mainly marketing toward your friends.

"Let's say somebody likes Twinkies on Facebook," he says. "Twinkies will then buy an ad from Facebook. And the ad will say, 'Joe Turow likes Twinkies.' And it will be called a sponsored story, and it will go to all of my friends on the side of their Facebook page."

Companies hope that your friends' preferences will also become your preferences, Turow says.

"It's implicit that if 'Joe Turow likes Twinkies' you might like them, too," he says.

Sites like YouTube, meanwhile, are displaying advertisements before and during videos. YouTube — which is owned by Google — is in the process of developing more than 100 professional content streams with partners like Madonna, Shaquille O'Neal and Anthony Zuiker, the creator of the CSI TV series. The company hopes the new professional videos will keep YouTube's visitors on the site longer — and attract more advertising dollars.

"Advertisers are currently wary about putting ads around nonprofessional videos," Turow says, "so video on the Internet is a big area."

But whether or not ads are effective, he says, is still a murky issue.

"It used to be that [successful advertisements were measured] in click-throughs," he says. "But a lot of people point out that people may make up their minds after seeing the ads over time without clicking. Only a very small percentage clicks. So [media] online says, 'We don't have to prove clicks. There are other ways an ad proves its power.' "

Advertisers today try to figure out the attribution, or value, of a stream of advertisements during a person's hunt for a product, he says.

"If you're going after shoes, for example, it isn't just the final click that caused you [to buy the shoes] but maybe 15 different searches, seeing different kinds of ads," he says. "And can [they] track you while you do that? That's what I call the holy grail."

Privacy Concerns

Turow says this new age of digital advertising raises concerns about what companies know about people, and what they can then do with that information.

"Some of them are really essential things, like, do you have diabetes? Are you a certain age that they may not want to hire you? What's your financial situation?" he says. "Will you be able to pay your mortgage?"

Turow says companies can then make certain inferences about people's behavior.

"I'm concerned about ... social discrimination," he says. "... In an everyday world where companies are deciding [how] I'm targeted, making up pictures about me, I'm getting different ads and different discounts and different maps of even where I might sit in an airplane based on what they think about me."

In the future, Turow says, you might be placed into "reputation silos" by advertisers, who will then market products to you accordingly.

"It has a lot of ramifications of how we see ourselves and how we see other people," he says. "... And this is part of another issue we have to think about, which is information respect. Companies that don't respect our information and where it comes from are not respecting us, and I think moving into this new world, we have to have a situation where human beings define their own ability to be themselves."

Interview Highlights

On the categories advertisers use to track you online

"Most of them have to do with demographics like age and gender and income. Some of them have to do with where you live, which can be very specific to particular neighborhoods sometimes. Some of them are weird, like socially organic eaters, but that has to do more with how companies make inferences about how you act. ... Go to a company called Acxiom on the Web. You will see a catalog of maybe 100 pages of the kinds of things that this company sells about all of us. They sell whether you look for diabetic stuff online, whether you're interested in orthopedic products, whether you've gone on vacation. They will sell what kinds of credit cards you have. And all of this is perfectly legal, and it can be used for online targeting as well as offline targeting."

On how apps can store and transmit information in your phone's address book

"It remains to be seen how many companies took out and take out that data and what is done with them, but you can see that it could give you an enormous amount of stuff. ... You can look at a person's camera and actually turn it on if you wanted to. A person might notice that the camera's on, but you could look at his friends or her friends and identify them if you wanted to, in a certain kind of world. You could look at the person's photos, contact lists. That's potentially the case with what people have been saying about the Apple iOS."

On Twitter and other companies gathering information from people's address books on their iPhones

"Social media is all about relationships. If you want to find people's relationships, an address book is the best place to go. It's like if you want to rob a bank, go where the money is."

On Facebook

"The amount of money Facebook gets per user from advertisers is not nearly the amount of money that Google gets. But the potential is there, and that's why Wall Street has been going after them.

"They gather everything that you do on Facebook. Facebook scarfs it all up. We know that Facebook has the ability and does target you on their website in an enormous number of ways. They don't give your name to any of the advertisers — it's all done anonymously. I'm not a fan of the distinction between anonymity and nonanonymity. ... If you're Joe Schmoe online or they know your real name or they give you an identification number — and so much of our lives is done online — in the end it doesn't matter. You're treated like a person who they know with all of the possible discriminatory activities we've talked about."

On online media

"I would argue that the 20th century taught people that content is cheap. Because on television and radio it was free, in newspaper and magazines, they got huge amounts of stuff paying very little. And as a consequence, when the world starts changing and there's a lot more competition because there's no longer one place to get news in print, the notion of paying for a lot of people became anathema."

On European privacy policies and an upcoming U.S. privacy policy

"They believe in privacy as [a] human right. And that's the interesting thing about how [the upcoming] Commerce Department report is positioned: as a right. There are some advocates who don't like what they see in the policy because they think it's too loose. But the very fact that it's called a right is interesting rhetorically. Some people would say they're moving in the right direction."

On data-mining and politics

"Politicians want to get votes. And they have begun to realize what consumer products companies realize: that if you get a lot of information about people, you can predict how they might act or what they might believe, even to the point [of thinking] 'What kind of car do people who might vote Republican have vs. Democrats?' And the more data points you have, the belief system is, the more likelihood that you can get on the right side of a person. So companies have evolved over the last few years that are essentially data-mining companies for various political organizations. Even the Obama campaign is perceived to be at the forefront of this stuff. If you go to their privacy policy, they take everything. When people give information about themselves for whatever reason on the Obama website, [the campaign] keeps it, they use it, they buy other information about you if they want. And on their privacy policy, it says they might share it with political organizations they consider conducive."

Copyright 2012 National Public Radio. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We're moving away from the world of "Mad Men," in which Don Draper comes up with poetic TV ads with universal appeal. Sure, there are still Don Drapers out there, but in the new digital world, advertisers are trying to figure out how to tailor ads specifically to your needs and send those ads to you on your computer.

In order to know who you are and what you want, advertisers are trying to find out all about what you do on the Internet. They're buying information from data marketers who are finding ways to track you without you being aware of it through digital tracking tools like cookies.

Cookies are text files that allow marketers to recognize a computer and track the user's online movements. My guest, Joseph Turow, has been tracking the trackers, studying how you're being followed by data marketers and how advertisers are using that information. His new book is called "The Daily You: How the New Advertising Industry is Defining Your Identity and Your Worth." Turow is a professor of communication and associate dean for graduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania's Annenberg School.

Joseph Turow, welcome to FRESH AIR.

JOSEPH TUROW: Thank you.

GROSS: So I am unaware, usually, of how I'm being targeted by advertisers, on how I'm being tracked by advertisers. But one thing I am aware of, since it's very hard for me to find shoes that fit, I'm on shoe websites fairly often, sometimes I'll be on a site and suddenly all the shoes I've recently looked at are kind of circling around on a carousel, as if they're saying to me: Hey, you looked at me, you looked at me, you said you might buy me, so like buy me, like here I am, like buy me.

TUROW: That's great.

GROSS: Like you looked at me. And they just keep circling and circling and circling. Not such a big deal. I'm sure you can top me.

TUROW: Well, I can, actually. Most recently, on Valentine's Day, I sent my wife a Valentine's Day card through Blue Mountain, which is what I pay for, and it was card where a walrus talks to her and says, you know, Happy Valentine's Day.

Then she sent me a return saying thank you. I clicked on what she received, and I have a program on my computer called Ghostery, which lets me know what the companies that put cookies on - and tags on my machine are doing. And I got 15 companies that were tracking the fact that I had opened that Valentine's Day card.

It's quite possible she had companies doing exactly the same thing on her end. And we don't know what these companies are tracking, but I know them, and they cover people from across the Web. Some of them are really big companies like Microsoft and DoubleClick, which is owned by Google. Some of them are companies that most people outside the industry never heard of.

But these are tracking everything you do, including, obviously, Valentine's Day cards.

GROSS: So what would they do with that information? They know that you sent somebody a Valentine's Day card. They may or may not know that somebody is your wife.

TUROW: Uh-huh. They could - if it's possible to know that my wife opened it, and it came from me, they could track that relationship, and there are companies that specify and are really interested in relationships building and whether you do that.

They might make inferences about me and romance. They might make inferences, right or wrong, about my age. They might think about - they might know where I did this because they have some sense of where my computer is, my IP address. There are a lot of things that they can infer about me even from this.

But it's not this one seemingly trivial issue. If you combine that with what they know about me everywhere else I go and what they may have bought about me, some of these companies, from outside companies that track what people do offline, even anonymously, eventually they have hundreds of data points that could be used to sell me things, to send me discounts, ultimately even to change the entertainment agenda and news agenda that I get.

GROSS: So your book is in part about a whole new industry of ad buying, an industry that's collecting information and then targeting, very specifically, ads to potential customers, people that these companies think are perfect for the product.

TUROW: Yes.

GROSS: And it's much more targeted, advertising is much more targeted than it's ever been. Like, how are marketers collecting so much information about us?

TUROW: There are a lot of different ways. Part of it is we're living in a digital world, and the importance of understanding that idea is that digits are transferable across platforms. So there are problems with some of what I'm going to say now, but in the Holy Grail vision of this, the idea is that what you do on mobile should be able to be connected to what you do on the Internet. What you do on the Internet should be able to be connected to what you do on your iPad. And eventually, and this is the real Holy Grail, all of this will converge on what you watch on television.

GROSS: Let me just back up a second. Like as users, we want all our devices to be interconnected.

TUROW: Right.

GROSS: But you're saying for advertisers this is really a gold mine.

TUROW: Yes, it is, and they say it that way. And it's not - what I'd like to point out is we're at the beginning of this new world. It's 15, 20 years old at the most. Think about how this is going to be 10, 15, 20 years from now.

GROSS: So you gave us an example of how you were being tracked when you sent your wife a Valentine's Day card. Give us some examples of what ads are coming to you.

TUROW: Well, I've gotten ads recently based on my age, OK? Particularly for some reason having to do with social dating sites, possibly...

GROSS: You're married, wait a minute.

TUROW: Yes, I'm married, but I have a student - and this is where things get really weird. I have a student who's doing research on social dating sites, and I've probably gone online to check some of the stuff that he's been doing, to look at some of his work, and somehow they've made inferences about me.

And I don't know exactly how they've gotten my age, but they're converging data around that, and I've been getting a bunch of things about marriage - about dating, I should say. The other things I've been getting have to do with the use of various news sites.

I was looking, for example, at buying a new lens for my camera, and most people have this experience where you get the same ad over and over wherever you go for the same thing. Now, it doesn't always work well even from their standpoint.

So for example, in this particular case I bought the lens, but I bought it over the phone.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So they don't know.

TUROW: They didn't know this. I bought it from the same company. So they kept this darn ad for a couple of weeks. So I guess the point is, this is not necessarily accuracy we're talking about. It's still very messy. Advertisers still are trying to figure this all out.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Joseph Turow. He's the author of the new book "The Daily You: How the New Advertising Industry is Defining Your Identity and Your Worth." And the new advertising industry he's talking about is targeted online advertising, how the advertisers get information from you and then target you with ads.

So let's talk about some of the state-of-the-art ways that have been developed in this new age. Let's start with Google, because they've been incredible innovators in the advertising world. When you Google something, on the right-hand side are ads. On the left-hand side is, like, the search stuff, but on the right-hand side what you usually get now is related ads.

TUROW: And that's where Google makes its great proportion of money, through paid ads.

GROSS: And how does that work?

TUROW: It's an auction process. They won't tell you their secret sauce. But basically let's say I'm an advertiser, and I'm interested in selling a certain kind of toy, OK? I bid for a key word. Let's say it's a car, a toy car. So I might write toy car, and if I win the bid, my ad shows up when people write the words toy car. OK?